|

|

Pulmonary Auscultatory Skills During Training in Internal Medicine and Family PracticeSALVATORE MANGIONE and LINDA Z. NIEMAN

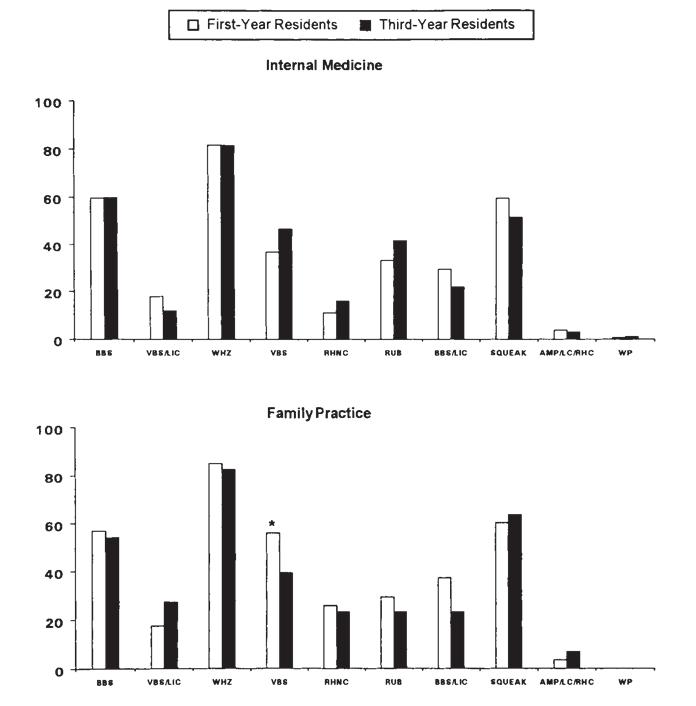

We conducted a multicenter, cross-sectional assessment of pulmonary auscultatory skills among med- ical students and housestaff. Our study included 194 medical students, 18 pulmonary fellows, and 656 generalists-in-training from 17 internal medicine and 23 family practice programs in the Mid- Atlantic area of the United States. All participants listened to 10 pulmonary events recorded directly from patients, and answered by completing a multiple choice questionnaire. Proficiency scores were expressed as the percentage of respondents per year and type of training who correctly identified each event. In addition, we calculated a series of cumulative scores for sound recognition, disease identification, and basic knowledge of lung auscultation. Trainees’ cumulative scores ranged from 0 to 85 for both internal medicine and family practice residents (median 40). On average, internal medicine and family practice trainees recognized less than half of all respiratory events, with little im- provement per year of training, and were not significantly better than medical students in their scores. Pulmonary fellows had the highest diagnostic and knowledge scores of all groups. These data indicate that there is very little difference in auscultatory proficiency between internal medicine and family practice trainees, and suggest the need for revisiting these time-honored skills during resi- dency training. Mangione S, Nieman LZ. Pulmonary auscultatory skills during training in in- ternal medicine and family practice. AM J RESPIR CRIT CARE MED 1999;159:1119–1124. The invention of the stethoscope was the brainchild of a di- minutive, asthmatic, and very shy French physician, con- fronted in 1816 with the “inadmissible” (1) task of placing his naked ear over the naked chest of a young female patient. A “cylinder” of rolled-up paper, subsequently made of wood, was the clever way out of this predicament, and the dawn of a new era in medical diagnosis. If heart sounds were the first acoustic events detected by Laennec’s cylinder, it was the lung that subsequently became the primary target of the stethoscope. In the decade preceding his premature death, Laennec used this tool extensively, cor- relating auscultatory findings with autopsy data and thus lay- ing the foundation for a clinicopathologic classification of lung sounds. He was so enamored of his little tool as to become known in Parisian medical circles as “the cylindromanic” (2). After Laennec’s death in 1826, most of the clinical interest in stethoscopy turned gradually toward the more complex area of cardiac auscultation. Only over the past two decades has this shift stopped and possibly reversed, thanks to the ap- plication of computer technology to the analysis of respiratory sounds. This in turn has led to the creation of the International Lung Sound Association (ILSA), whose activities have con- sisted of a yearly international research conference and even the maintenance of a website, inclusive of respiratory sounds that can be downloaded at no cost. This renaissance of lung auscultation was recently acknowledged by a series of editori- als in leading pulmonary and physiology journals (3–5), by a state of the art review (6), and by the European Commission’s support of a multinational project dedicated to the standard- ization of computerized respiratory sound analysis (CORSA project [Contract No. BMH1-CT94-0928/DG12SSMA]). Although applied research in the field of pulmonary aus- cultation has grown sharply, it is not clear whether this rekin- dling has translated into improved clinical skills or educational practices during training. There is actually evidence to the contrary. For example, in a national survey of internal medi- cine and family practice residencies, we recently found that only one out of 10 programs in the United States offered any structured teaching of pulmonary auscultation (7) (as opposed to one out of four programs for cardiac auscultation [8]), and that program directors still consistently attributed much less importance to this skill than to cardiac auscultation. To better elucidate whether the decreased emphasis given to lung auscultation during residency might have actually led to a lesser degree of proficiency among trainees than that for cardiac auscultation, we surveyed the respiratory auscultatory skills of a large group of internal medicine and family practice residents of the Mid-Atlantic area, and compared their accu- racy with that of a control group of medical students and pul- monary fellows. METHODS We assessed the auscultatory skills of 656 generalists-in-training. These participants comprised 404 trainees in internal medicine and 252 trainees in family practice, from 17 and 23 residency programs, re- spectively, in the Mid-Atlantic area. Ten of the 17 internal medicine programs were located in Pennsylvania (of these, nine were in Phila- delphia); the remaining seven internal medicine programs were based in New Jersey, Maryland (two), Delaware, Washington, DC (two), and New York State. Eighteen of the 23 family practice residency pro- grams were located in Pennsylvania. The remaining five were located in Maryland (two), Delaware, Washington, DC, and New York State. Twelve of the 17 internal medicine programs from which trainees were tested were based in university hospitals and five were in non- university hospitals. Thirteen of the 23 family practice programs tested were suburban and 10 were rural. In addition to these generalists-in-training, we included in our study: (1) 194 third and fourth year medical students (whose profi- ciency provided a baseline comparison for the trainees’ performance); and (2) 18 fellows in pulmonary and critical care medicine from six different training programs (whose proficiency provided a high-end comparison for the trainees’ performance). Attitudes Survey Participants also completed a one-page attitude questionnaire. Thi component of our study was administered prior to the proficienc testing. This 13-item questionnaire assessed the residents’ self-moti vated learning and personal interest in pulmonary auscultation. Item included the importance attributed to lung auscultation, the need t devote more time to its teaching during medical training, the amoun of auscultatory instruction received during medical school or res dency, and the respondent’s confidence with his or her own pulmo nary auscultatory skills. Other variables assessed whether respondent had any special interest in music and whether they could play a musi cal instrument. We included these two items to determine whethe any “training of the ear,” independent of the motives for pursuing it might have helped achieve a greater auscultatory proficiency. DISCUSSION This study was part of a two-pronged investigation by the American Academy of Family Physicians, aimed at assessing the status of two very important bedside skills: cardiac and pulmonary auscultation. Proficiency data relative to cardiac auscultation were reported in a previous publication (9). Time-honored skills such as chest auscultation are essential filters for a more intelligent use of diagnostic technology (10– 12). As a result, they have become the focus of recent atten- tion since the advent of managed care and its renewed empha- sis on more ambulatory and cost-effective medical care. Yet bedside skills such as auscultation still remain largely ignored in residency curricula. Structured teaching of lung ausculta- tion, for example, is almost absent during primary-care train- ing (7). The teaching of cardiac auscultation is also very much underrepresented (8). A decreased emphasis during training and the ever increasing reliance on technology-based diagno- sis are probably responsible for the poor auscultatory profi- ciency we found among trainees.Although trainees’ proficiency was generally poor, we did ind a significant difference between accuracy in pulmonary uscultation (40% on average) and accuracy in cardiac auscul- ation (20% on average). This difference occurred, paradoxi- ally, despite the lesser extent of teaching devoted to lung aus- ultation during residency training. A probable reason for the ifference is that lung sounds are easier to identify. This may lso be the reason why trainees had greater confidence in their espiratory auscultatory skills as opposed to their cardiac aus- ultatory skills.<\p>

Lung auscultation is easier than cardiac auscultation be- ause it allows more time for the identification of less numer- us and more easily audible acoustic signals. Sounds of the ungs are: (1) higher-pitched; (2) scattered across a longer ime interval (2 to 3 s for the average respiratory cycle, as ompared with 0.8 s for the average cardiac cycle); and (3) arely present as more than two or three acoustic findings per vent (whereas in cardiac auscultation, there may be as many s four to five findings in a cardiac cycle of only 0.8 s). Not sur- risingly, our trainees had the greatest difficulty when chal- enged by respiratory events containing two or more acoustic indings. |