Executive

Summary

Business

process management (BPM) promises to help organizations orchestrate their

people and systems in order to conduct business more efficiently and

effectively. BPM can deliver improved process efficiency as well as better

visibility into business operations. Organizations that have invested in BPM

methodologies and technologies see rapid return on their investments and derive

greater value from their existing systems. In fact, of TIBCO customers

responding to a recent survey conducted by Intercai Mondiale:

• 100% increased

productivity

• 95% improved

quality of service

• 82% reduced

operating costs

• 82% saw

faster process cycle times

In

addition, more than 80% of respondents reduced operating costs and IT costs,

increased productivity, and improved their quality of service beyond their

expectations.

The

results above, while impressive, only scratch the surface of what can be

achieved with BPM. Many of these results represent the “low-hanging

fruit,” benefits

that were realized due to automation of fairly simple processes. In order to

extract value from BPM initiatives over the long term, organizations need to be

able to model and execute highly complex business processes that evolved in

response to a highly unpredictable business climate. This can be difficult to

accomplish using traditional BPM approaches that lend themselves better to more

static processes and provide visibility only at the highest level of the

process. Instead, organizations need to adopt a new approach to building

business processes: goal-driven business process management.

Goal-driven

BPM is an approach that makes the development and identification of business

processes a more intuitive and natural activity. It uses familiar organizational

concepts such as goals and the steps taken to achieve those goals (sub-goals),

provides granular visibility into sub-goal progress, and allows processes to

intelligently change course as events unfold. When managed and deployed

appropriately, goal-driven BPM delivers significant benefits, including:

•

Faster,

less expensive process creation via process component reuse

•

Significant

business user engagement in process design

•

A

better context for process monitoring

•

The

agility to fix more problems as they occur rather than after the fact

•

The

ability to dynamically adapt to new business conditions

This

whitepaper provides an overview of goal-driven BPM: the underlying concepts,

management practices, basic implementation methodology, and characteristics of

the technology that effectively support this new approach. It outlines the benefits

you can achieve with goal-driven BPM and discusses how the methodology and its

supporting technology will bring a new level of agility and flexibility to your

business.

Introduction

Today’s

business climate is notoriously unpredictable. Businesses prepare for one type

of weather, and a different type materializes. The cost of preparing - or not

preparing - for inclement weather can be extremely costly.

Business

process management (BPM), both the management practice and the software tools

that facilitate it, evolved to help organizations address this constantly

changing environment. BPM has helped organizations:

•

Improve

productivity by automating many key processes

•

Improve

customer service and compliance by providing visibility into processes

•

Improve

the overall flexibility of business processes through a variety of different

approaches

But,

as with anything else in business, there is no completely evolved state for a

business process. It must continue to transform to help enterprises meet the

newest demands of the market. The market is rarely satisfied for long. Quickly

and inevitably the old refrain returns: newer, faster, better.

What

more can be done? There are already a myriad of technologies and best practices

to help organizations act quickly on up-to-the-minute information. However, as

more organizations adopt these solutions, previously cutting-edge technologies

quickly become a baseline cost of doing business. The most responsive and

competitive companies now need more if they are to satisfy their customers and

stay ahead of the competition.

Part

of the problem is that organizations are able to act on up-to-the-minute

information only in so far as the possible action is already built into the

process. Greater process flexibility is needed if these organizations are to

become truly responsive - to move from reactive to predictive. It is imperative

to shift from inherently static processes - processes that are discoverable and

understandable, evolving relatively slowly over time - to processes that are

complex, dynamic, and predictive - actually evolving during execution to meet

previously unknown requirements.

Achieving

such a monumental shift requires a new approach to building business processes:

goal-driven business process management.

Goal-driven

BPM is an approach that makes the development and identification of business

processes a more intuitive and natural activity. The world is goal driven; we

organize our lives, both personal and professional, around goals. When these

goals are large, we break them down into sub-goals that take us a step at a

time to our final objective. Often we work back from the goal to our current

position in order to identify the best route to that goal. For any scenario,

there are likely a variety of “best”

options, the actual best depending on the variables of the situation.

Goal-driven BPM treats processes in the same manner. When managed and deployed

appropriately, goal-driven BPM provides today’s

most competitive organizations with the flexibility and visibility they need to

win.

What

Is the Reward for Achieving Your Goal?

The benefits

described below represent what can be gained from a successful implementation

of goal-driven BPM. A successful implementation has two critical and

complementary parts, discussed later in this paper. The first part is

methodology and the second technology. If both of these are successfully

applied, organizations can expect the following benefits from goal-driven BPM.

FASTER,

LESS EXPENSIVE PROCESS CREATION VIA PROCESS COMPONENT REUSE

The

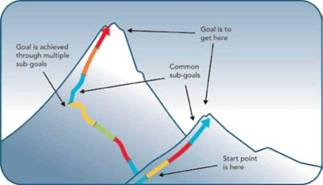

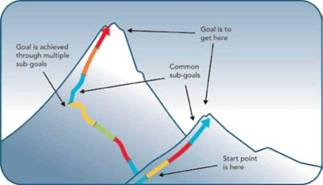

following metaphor explains the key premise behind goal-driven BPM. When

planning a route to the top of a mountain, when no established trail exists

(goal = reach top of mountain), one approach is to consider the route from the

top of the mountain, scoping out the safest and simplest route at each stage

(sub-goal). Each section will present different conditions (screed, rock wall,

glacier, and so on). When each of these conditions is encountered, a standard

technique (process) is employed to traverse that section (achieve the

sub-goal). The complete set of sub-goals, and the associated processes required

to complete each sub-goal, provide a complete plan for achieving the main goal,

in this case reaching the top of the mountain. Having learned the required

techniques (identified the processes); these techniques can be reused in

similar situations to achieve different goals. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure

1. Different colors on the path represent the standard techniques (processes)

that can be reused in similar situations to achieve different goals

By organizing processes around goals,

that is “what

is to be achieved” rather than “what

is to be done,”

goal-driven BPM helps organizations achieve needed flexibility. Breaking down

business processes into sub-goals is critical to this flexibility. The

collection of discrete sub-goals makes up the building blocks available to a

process designer. Just as the mountain climber increases the number of

mountains she can climb by expanding her skill set, so expanding the set of

sub-goals increases the number of new processes that can be created by

combining a number of different sub-goals. Creation of a process that achieves

a goal out of existing sub-goals requires no new effort. The processes needed

to create each of those sub-goals are already defined. In the context of this

paper, they will be referred to as process components.

FACILITATE

BUSINESS-USER ENGAGEMENT

A key

part of the flexibility provided by a goal-driven approach to BPM is that it

puts complex process design in the hands of business users, in a way that is

familiar to them. Designing a complex process using constructs such as dynamic

sub-procedures may or may not be familiar to a business person. However, the

concept of reaching a goal by setting several milestones needed to achieve that

goal is something familiar to us all, regardless of profession. Goal-driven BPM

provides business people with intuitive building blocks for creating new

processes to deliver new products, groups of products, services, and so on. The

ease with which this can be done means that organizations can act on

opportunities or threats as soon as they are identified.

BETTER

CONTEXT FOR PROCESS MONITORING

In addition to making the creation of

new processes quick and painless, a goal-driven approach to BPM makes it

possible to monitor processes at a level with adequate visibility to act on

problems and change course in a timely manner. Breaking down processes into

logical discrete sub-goals makes it possible to monitor processes at the

sub-goal level. Monitoring a process at this level can be more valuable than

monitoring the process either at the step or overall process level. This is

because if a milestone such as a sub-goal is missed, it can mean that the

entire process is in jeopardy of being completed on time. On the other hand,

late completion of a single step may not impact the timely completion of the

goal. If real-time visibility only gives us information about whether an entire

process finished behind schedule, it is alerting us to a problem that is

already beyond our control.

AGILE

BPM FIXES MORE PROBLEMS

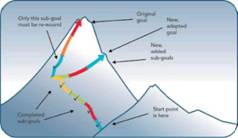

Once

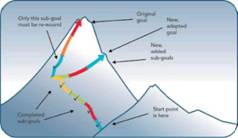

a problem is identified, a goal-driven approach to BPM makes it easier to fix.

Should our mountain climber encounter an impassable part of the mountain, she

will not go all the way back to the bottom of the mountain and start over,

rather, she will go back to the last part of her route that is in common with

whatever new route she decides on. BPM, when approached in a goal-driven

manner, works the same way. If a problem is identified that truly does

jeopardize the timely completion of a process or goal, the process can be

dynamically reconfigured in-fight. Rather than simply failing, the process

might intelligently find a different path. The running process can be wound

back to the last completed sub-goal in common with the new process, “undoing”

previously executed steps. This is illustrated in Figure 2

Figure

2. Modifying the target goal

THE

END STATE: DYNAMIC, ADAPTIVE BPM

In its most revolutionary incarnation, a

goal-driven approach to BPM makes it possible to do all of this automatically,

based on rules. For example, when a work order comes in, the appropriate

process components are selected to create the process, based on rules. If, at a

later point, a milestone is missed, an alert is triggered. Predictive

simulation identifies that the missed milestone will result in a delinquent

process, and rules dynamically identify the best course of remediation,

dynamically selecting the required process components. Through this process of

sense-and-respond incremental improvement, goal-driven BPM makes it possible to

create the most dynamic, agile, and responsive processes.

Getting

to Goal-Driven BPM

Similar to the mountain climber planning

his or her route to the top, achieving goal-driven BPM requires an organization

to break down its problems - key business processes - into bite-size pieces. To

do this effectively, the organization needs a comprehensive methodology with

associated BPM patterns designed for goal-driven BPM, as well as software that

directly and transparently supports these concepts.

Adopting

a Goal-Driven BPM Methodology

IDENTIFYING

GOALS AND SUB-GOALS

Goals are the objectives to be met by

the business as part of its day-to-day operation. These goals operate at many

different levels. Some sample business goals are “handle

an order”

(lower level) or “roll out infrastructure to the northwest

region”

(higher level). Though some types of goals will be common across many organizations

(for example, “reconcile

supplier billing”), many will be specific to an industry

and the organization itself.

Sub-goals represent the management of

the items of interest to the business. Once identified, each of these “items

of interest,” or

sub-goals, can be managed as a service, a discreet entity without dependencies

and able to be reused as required by any part of the business.

The

key to correctly identifying the items managed by a business is to identify all

of the tangible and intangible items directly or indirectly involved in the

day-to-day running of the business. Lists of intangible items may include such

things as contracts, policies, or services.

Incident

events, such as a withdrawal, a claim, a trade, a crash, or a holiday, may also

be of interest. Figure 3 provides examples of tangible and intangible items of

interest.

|

Intangible

Items

|

Tangible Items

|

|

•

Regulations

|

•

Employees

|

|

•

Trade

|

•

Customer

|

|

•

Price

|

•

Departments

|

|

•

Contracts

|

•

Fax machine

|

Figure

3: Examples of managed items involved in a securities trade

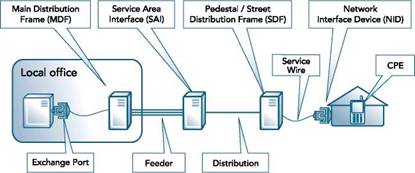

Tangible

items are generally easier to identify as these are the physical items involved

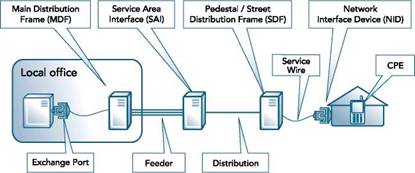

in the day-to-day running of the business. For example, for a

telecommunications provider they could include products, employees, customers,

test equipment, wiring, departments, and so on. This is illustrated in Figure

4.

Figure

4: Examples of tangible items managed in the provision of a telephone line

Business analysis techniques, such as

business conceptual and structural modeling, can help with the identification

of the tangible and intangible items likely to be managed by business

processes. When an exhaustive list of managed items has been identified, it is

then possible to optimize this list by pruning those items that are only

tangentially involved in the business process and by identifying suitable

abstractions that cover whole classes of the items identified. Care should be

taken not to over-optimize this list, lest the managed items be abstracted into

generic uselessness.

Each

goal or sub-goal then manages a single item or a set of highly cohesive related

items. This results in discrete processes that are cleaner and more likely to

be reusable. Because of the discrete nature of these “process

components,” it

is also possible to expose them as “services,” with

simple, clean interfaces.

IDENTIFYING

SUB-GOAL CANDIDATES FOR REUSE

Goal orientation of business processes

is a powerful concept. Its value is further magnified by the possibility for

greater process reuse. This is possible due to the encapsulation of items

significant to the business as services that are available for reuse.

Business

is organized around two main axes: vertical business segments, within which

end-to-end business processes exist, and horizontal, business-spanning

functions that cross these segments. This is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure

5: An example of a logical business organization

These horizontal functions may represent

physical organizations, such as a department, or logical organizations, such as

a set of related roles that span the business. Each horizontal area has specific

items that it manages and, as such, has its own set of “process

components.”

Goal-driven

BPM allows for the identification of the sub-goals associated with end-to-end

business processes. Once sub-goals are identified, it is easy to identify those

that are common across vertical segments or horizontal functions and therefore

candidates for reuse. Frequently, the items managed by the horizontal functions

participate in the achievement of many of the organization’s

goals for the vertical segments. Reuse of goals is most likely with the more

generic horizontal functions (such as the financial function in the example

above), but other reuse is also possible.

FORMULATION

OF END-TO-END BUSINESS PROCESSES: ACHIEVING GOALS

Once process components are identified,

they can be assembled into groups of components that achieve a desired business

goal. The components are then sequenced and scheduled in an order that

facilitates the completion of the goal or process. To achieve the greatest flexibility,

it is important that the constituent process components have no dependencies

such as loops or conditional parts. For example, if the process were building a

house and two process components were laying the foundation and building the

walls, whereas the foundation must be built before the walls, what constitutes

the foundation should be irrelevant to building the walls.

Key to the success of this approach is

the adoption of a suitable concept or metaphor that makes the combination of

process components understandable to the business analyst. The project plan

provides such a metaphor. Tasks in the plan represent the independently defined

process components. The tasks are then sequenced appropriated, as in the

example above, where the foundation must be completed before the walls of the

house are erected.

Deploying

Technology to Support Goal-Driven BPM

WHY

DO YOU NEED TECHNOLOGY?

A goal-driven BPM methodology used

during the design of business processes is beneficial regardless of how the

organization implements the methodology. However, the advantage of using this

approach is greatly reduced when used without BPM software that fully supports

goal-driven BPM. Specifically:

• BPM

reuse is restricted: Goal-driven BPM software can enforce many of the process

attributes that are necessary for reuse. Without checks for less optimal

process design, organizations will find fewer opportunities for reuse.

• Dynamic

BPM is not possible: Without supporting software, goal-driven BPM is reduced to

a design-time-only concept. Individual processes will not be able to adapt when

real-world conditions do not follow a single pre-defined path.

• Empowerment

of business users is restricted: Building on-demand business processes as an

intrinsic activity of a business user’s day-to-day

work is only possible using software designed for that user’s

skill set. Without appropriate software, business process development

is usually a technical activity, beyond the ability of most business users.

For software to effectively facilitate

goal-driven BPM, it must provide support for the following activities.

• Organize

business processes around goals to be achieved by the business: Example goals

are: deliver a product, close a deal, resolve an exception, and so on.

• Determine

sub-goals required to achieve the desired end goal: Identify the required

sub-goals by working back from the end goal one step at a time to the starting

point or current position. The current position can be defined by many things,

for example: number of outstanding deals, credit status of the subject

customer, and so on.

• Allow

the end goal to change part way through its fulfillment: For a business to

achieve the required level of agility it must be possible to change direction

or adapt goals quickly. For example, a customer status may change while a

process is in motion.

It is important to note that though

sub-processes (dynamic or otherwise) and business rules are powerful facilities

on their own, they are insufficient to support the dynamic nature of

goal-driven BPM. Sub-processes (even dynamic ones) tend to have dependencies on

one another that limit their flexibility. Also, a process can only incorporate

those sub-processes that are explicitly included in the definition of that

process. Therefore, if the goal of a process changes and requires a sub-process

that was not included during the definition of the process, it would be very

difficult and inefficient to add the sub-process needed to achieve the new

goal. Finally, sub-processes are not time aware, limiting the complexity of the

processes to which they can be applied. To overcome each of these shortcomings,

specific software is required that directly supports the concept of

goal-driven, dynamic BPM. For a more technical description of the limitations

of dynamic sub-processes, see Appendix 1.

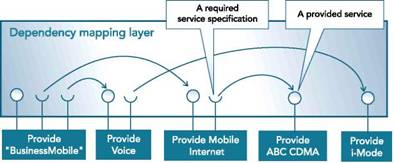

THE

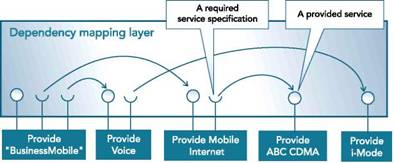

KEY TO GOAL-DRIVEN BPM: THE DEPENDENCY MAPPING LAYER

In order to get the desired level

of reuse it is necessary to break the dependencies between the abstract

higher-level processes and the more specific lower-level processes. This can be

done through a process dependency mapping layer that is external to the

participating processes. This layer maps the abstract services required by a

process onto the actual services provided by each sub-process. This is

illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure

6: Processes organized as services

Simple, dynamic sub-processes are not

sufficient to solve this problem as the process itself would still need to

determine the sub-process to invoke at runtime. Though this reduces the degree

of dependency, it does not eliminate it. It is still likely that an overarching

process will need to be modified when a new sub-process capable of providing

one of its required services is made available. In any case, the process itself

is made more complex by the requirement that it orchestrate its own required

services.

Where highly cohesive areas of a process

require decomposition, or a generic, relatively static process element is

required, sub-processes are a powerful and appropriate tool to use. Where reuse

is required in a more fluid environment, such as dynamic, goal-driven BPM, a

more abstract mapping capability is required.

PUTTING

IT ALL TOGETHER: CREATING EXECUTION PLANS

Execution plans represent an overarching

process created from process components. An effective tool for goal-driven BPM

will use a simple metaphor, such as a project plan, to help users create

execution plans. An execution plan contains a wealth of information. The

sequence of process components is one part, of course, but execution plans also

define restrictions such as “A cannot start

until B is finished,” or “A

must start simultaneously with B,” or “A

must start two hours after B starts.” Each task

within an execution plan also has information that is used to monitor the

process during execution. Every task has a set of values appended during

process design that help to identify when that task or possibly the entire plan

is in jeopardy.

Execution

plans can be generated in three ways:

•

Manual Creation: Processes can be created manually by business users

immediately prior to runtime. This type of process creation is used either to

create a template or, in exceptional cases, where no template or rules exist to

handle the request. It is not expected to be the standard

process for execution plan generation, as it can be time-consuming. The

required process components are selected from a library; the dependencies,

temporal or otherwise, are defined; and the various alarm values are assigned

to each task.

•

Template

Selection: Templates are created manually (as described above), then stored for

future use. This is the way that the majority of execution plans are created,

as a best practice is to identify most common requests and create execution

templates for them; only the exceptions would need to be handled manually. When

a new request comes in, the pertinent information from that request is used by

a rules engine to select the appropriate template. The template already has all

tasks sequenced, dependencies identified, and alarm values included.

•

Automated

Execution Plan Generation: An advanced form of goal-driven BPM is automatic

process development. Organizations would use this type of execution plan

generation if their business processes require significant customization for

most requests, or are otherwise fluid, changing frequently. In such an

environment, the end goal of a process will depend on the variables present at

the point

of

execution and may change if those variables change during the process of

execution. Defining processes or execution plan templates to handle all the

combinations of these variables may be prohibitively expensive. Consider the

example of order management within a telecommunications operator. In excess of

100 products could be offered by such an operator. Customers can order any

combination of these products at any one time. Even if the unlikely

combinations of products are excluded, this still results in the requirement

for several thousand business processes (or templates) to fulfill the remaining

combinations! The solution is to define the sets of process components for each

process and then separately define the optimization rules for their

combination.

MONITORING

THE EXECUTION PLAN

One of the most important aspects of

goal-driven BPM software is the visibility it provides into running execution

plans. Without this visibility, there is little need for the flexibility

provided. If you don’t know that a problem is occurring, you

certainly don’t

know what to do to fix it.

Goal-driven

BPM software should be time aware. This time awareness enables it to monitor

service level agreements (SLAs) associated with overall goal achievement (end-to-end

business processes) and key performance indicators (KPIs) associated with the

process components that make up the end-to-end process.

Process

component KPIs are monitored by tracking the timeliness of each process

component. This allows the prediction of fixed milestones that will most likely

not be met and the monitoring of projected completion time of processes that

constitute the SLA for the end-to-end process. Users are alerted to execution

plans that are in or near jeopardy. Action can then be taken to avoid or

ameliorate the problem.

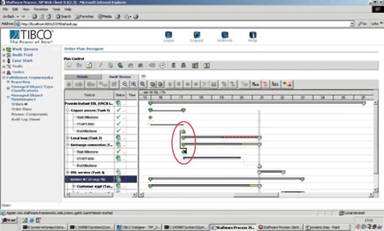

For

example, Figure 7 shows an execution plan developed with TIBCO iProcess™ Conductor,

a component of TIBCO’s BPM suite. The plan provides an

intuitive view of each process component, its dependencies, and current status.

The real-time status of the plan is marked by the light grey vertical line in

the center. An example of a dependency is circled in red, showing that task 2

may not start until task 1 has completed. The predicted and actual durations of

every process component are also shown. Jeopardy status is intuitively

displayed: red areas denote existing problems and yellow areas potential

problems.

Figure

7: iProcess Conductor In-Flight Execution Plan

Should

it be determined that the jeopardy status of task 2 jeopardizes the entire

plan, the user may decide to modify the process in-fight or completely change

the goal. If the company has architected its business processes for automatic

execution plan generation, this plan could also be dynamically reconfigured,

based on the pre-defined rules.

Conclusion

Goal-driven

BPM, supported both by an effective methodology and technology, provides

organizations with a new level of agility to support an unpredictable business

environment. It delivers significant benefits, including:

•

Faster,

less expensive process creation via process component reuse

•

Significant

business user engagement in process design

•

A

better context for process monitoring

•

The

agility to fix more problems as they occur rather than after the fact

•

The

ability to dynamically adapt to new business conditions

Goal-driven

BPM mirrors the approach we take to goals in our own lives and lends itself to

business user involvement in the creation and management of processes. While

intuitive to implement, goal-driven BPM makes it possible to create highly

complex processes with involved temporal dependencies between process

components.

When

evaluating technologies to support goal-driven BPM, organizations should look

for a solution that:

•

Supports

both business and technical users with tools appropriate to their skills and

roles

•

Breaks

processes down into goals and sub-goals, with an abstraction layer to minimize

dependencies

•

Facilitates

sub-goal reuse

•

Tracks

processes at the sub-goal level in order to find and fix problems before it’s too

late

•

Takes

action to adapt to events as they occur, even in the middle of a running

process

TIBCO

has over 15 years experience in providing BPM solutions and has delivered the

value of BPM to over 500,000 users at 800 companies. Contact us to start a

dialogue on how goal-driven BPM can significantly improve process management

for your organization.

About

TIBCO iProcess Suite

TIBCO

iProcess™

Suite software enables business users and IT staff to implement goal-driven BPM

while collaborating on the modeling, execution, and continuous improvement of

business processes that span their organization. It is a rich suite of

application modules with functionality designed to help organizations create

business processes of whatever complexity they require. The components of the

suite are: a business process modeling and simulation tool, a business rules

engine, an integration platform, an engine for executing processes, real-time

process monitoring, an end user workspace for process participants, and an

analytics tool for analyzing processes.

Using

TIBCO iProcess Suite, organizations can break down processes into discrete,

coherent components that facilitate reuse and fast process design and

re-design. These components map logically to sub-goals that are concatenated to

achieve a larger goal. TIBCO iProcess Conductor, along with TIBCO iProcess

Engine, is able to dynamically combine a set of process components associated

with required sub-goals, applying optimization as necessary and creating

real-time visibility at the process component level. The fact that iProcess

Conductor is time-aware means that if deadlines are missed as a running process

progresses, the expected path can be predicted. If the process is in jeopardy,

users will be alerted to that fact and can then adapt the process to avoid or

mitigate any problems.

With

TIBCO iProcess Suite, organizations achieve:

•

The

highest level of flexibility to address the complexities of today’s

business problems

•

Optimal

efficiency and effectiveness with goal-driven business processes that can

intelligently adapt to current conditions

•

Ability

to break processes down into goals and sub-goals, with an abstraction layer to

minimize dependencies

•

Better

business process design with intuitive tools designed for business users

•

High

levels of process reuse for maximum ROI

Appendix

1

Why

Sub-Processes Are Not Sufficient to Enable Goal-Driven BPM

Sub-processes

are a powerful facility for breaking down business processes into manageable

chunks. When using sub-processes, a contiguous business process is broken down

into a hierarchical set of sub-processes that can be represented as a tree. For

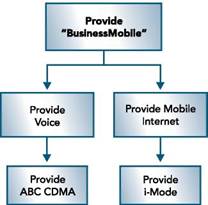

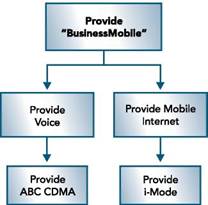

example, a process to provide a mobile telephony product for a Mobile Virtual

Network Operator (MVNO) could be broken down as shown in Figure 8:

Figure

8: A process to provide a domestic mobile telephony product

The “provide

voice” and “provide

mobile internet” sub-processes are largely generic

(dealing with billing configuration, for example); they invoke further

sub-processes to deal with the specifics of providing the actual service from

the provider used by the MVNO. In this case, these services are GSM, WAP and

MMS.

Figure

9 shows another product provided by the same MVNO. This is a product intended

for business users. It also consists of voice and mobile internet services, but

the method of delivery and the providers that are used are different.

Unfortunately the opportunity for reuse is restricted in this case because the

processes are dependent on sub-processes that provide the wrong specific

services. This is not a process versioning issue as both products are being

provided by the MVNO at the same time.

Figure

9: Opportunity for reuse is restricted