Decision-making is one of the defining characteristics of leadership. It’s core to the job description. Making decisions is what managers and leaders are paid to do. Yet, there isn’t a day that goes by that you don’t read something in the news or the business press that makes you wonder, “What were they thinking?” or “Who actually made that decision?” That’s probably always been the case, but it seems exponentially more so in the opening decade of the new millennium where everything seems marked with, “too big, too fast, too much, and too soon.”

The reality seems to be that most organizations aren’t overrun by good decision makers, yet alone great ones. When asked, people don’t easily point to what they regard as great decisions. Stories of bad decisions and bad decision-making come much more readily to mind.

Some of that is due to our tendency to notice and recall exceptions vs. all the times things go as planned. For example, you’ve walked along side buildings more times than you could possibly count. Yet you remember vividly the one time you got nailed by a pigeon overhead.

That’s how we are about bad decisions. We’re also that way because the really bad ones tend to really hurt.

It’s not that people don’t have the capacity to make high-quality decisions in them. Decision-making is a distinctly human activity. It’s what that great, big frontal lobe is for. We all make decisions all the time.

But the fact that we’re hard-wired to make decisions doesn’t by itself make us good decision-makers. That takes discipline: discipline to do at least four things all the time and well.

- Realize when and why you need to make a decision.

- Declare the decision: decide what the decision is, how you’ll work it, and who should be involved.

- Work the decision: generate a complete set of alternatives, gather the information you need to understand the possibilities and probabilities, and ultimately make a choice that best fits your values.

- Commit resources and act.

Not everyone does those four things consistently or consistently well. We’ve worked with a lot of leaders and managers in some of the most widely regarded companies in the world and our observation is that most people don’t. In fact, the distribution generally looks something like this:

- There are some really wretched decision makers. For them, a good outcome is usually a matter of luck.

- There are a lot of people who are reasonably competent decision makers. Their decision processes aren’t great, but they’re not bad, and the outcomes they experience track accordingly.

- There is a small group of people who could be described as “good decision makers” These people are proactive and decision oriented. They’re able to focus attention on what’s important and critical. They know how to break a decision down into logical parts. They know how to work each of those parts in a high quality way. They know how to deal with possibilities and probabilities. They’re able to see opportunities where others see problems. They’re able to make quality choices in the face of uncertainty. They’re able to turn thought into action.

- There is a sprinkling of people we’d describe as great decision makers. Like other good decision makers, these people consistently make high quality decisions. Their “greatness”, a word that is probably way overused, comes from their ability to create the dynamics needed to ensure that the people in their organizations can do the same.

Good and great decision makers expect high quality outcomes and they’re generally not disappointed. When they are, it’s usually because of some random thunderbolt or some unforeseen dynamic, not because they didn’t do a good job of working the problem. There are exceptions to this syllogism. But over the long-term, we think the good decision/good outcome connection holds up, and the outliers have either not been in the job long enough for their bad decisions to catch up, or have been extraordinarily lucky.

A decision is a choice between two or more alternatives. If you only have one alternative, you do not have a decision.

Webster’s 9th Dictionary adds some richness to the idea of choice by introducing the idea of uncertainty. It has this to say about the word “decide”, the root of “decision”

Decide: to arrive at a solution that ends uncertainty or dispute. From Latin decidere which means to cut off.

A typical thesaurus might use words like accommodation, agreement, arrangement, choice, compromise, declaration, determination, outcome, preference, resolution, result, and verdict to try and give the concept of “decision” some dimension.

In our minds Webster’s definition and these potentially illuminating synonyms seem to miss the driving idea behind a decision. A decision as an irrevocable allocation of resource.

This is where the concept of attention comes in. Attention implies the use of resource. It means you actually allocate some time, money, effort—something—to turning your intentions into action.

The concept of irrevocability means commitment: putting time, money, and/or resource on the line to put your decision into action. Having decided, you’re not going to re-litigate your decision every time someone has a new thought. Getting to that point with confidence is what separates low quality decisions from high quality decisions, and mediocre decision makers from good and great ones.

Making High Quality Decisions

A high quality decision comes with a warrant: a guarantee. Not a guarantee of a certain outcome—remember this is the real world we’re talking about, and there are certain things that just aren’t knowable until after they happen—but a warranty that the process you used to arrive at a choice was a good one.

This level of confidence implies a process: a set of steps and rules that provide an assurance of thoroughness and rigor. This means breaking decisions down into component parts and doing one thing at a time.

Unless you’re unlike most people, it is your nature to do what you know how to do and to avoid what you don’t. That’s why you want a rational decision process: To defeat the natural behaviors and tendencies that can lead to low quality decisions.

Without a process, you are likely to drag decisions into your comfort zone, handling “this one” in exactly the same way you handled “that one,” even though this one and that one may have little in common. Without an organizational decision process, that same “stimulus/response, stay in your comfort zone” dynamic can easily become the predominate driver of your organization’s culture and effectiveness. As a leader, you’re either doomed to inspecting every decision, or to hoping that people don’t decide to do something stupid while you’re not watching.

With a process or framework, you have the mechanism you need to warrant the quality of your own decisions. Perhaps more importantly, you also have a common language and set of mental models that makes conversations about decisions more efficient and effective. This common understanding of decision processes, criteria, and roles avoids many of the common organizational decision traps, allowing people in your organizations to spend their conversational energies on creating better alternatives and validating assumptions and ultimately warranting their own decisions.

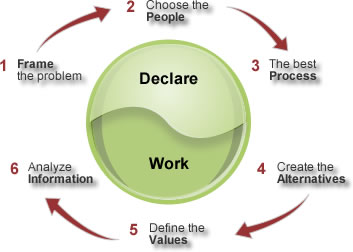

The framework we use for breaking down and working decisions of virtually any size and complexity begins with two large ideas: declaring a decision and working a decision. Each of those larger elements is then broken down into three sub components, or what we call Decision Points, which are illustrated in the following diagram.

Decision Point 1: Frame the problem. What are you deciding and why? What shouldn’t you be deciding and why? What’s not in the box is as important as what is. Without a good definition of the problem or opportunity to be worked, there is no possibility that you'll reliably reach a high quality decision.

Frames are mental structures we create to simplify and organize our lives. They help us reduce complexity. That’s the good news and the root of another set of problems. Says J. Edward Russo in his book, Winning Decisions, “Frames have enormous power. The way people frame a problem greatly influences the solution they will ultimately choose. And the frames that people or organizations routinely use for their problems control how they will react to almost everything they encounter.”

Decision Point 2: The Right People. If you're a single actor, or hold all the prerogatives of a dictator, this one is easy. It's just you. In other cases, you'll want to put some thought into declaring who needs to be involved in what steps of this decision. Too few, or miss some, and you risk the problems of rework, low adoption rate and poor buy in. Too many—too much inclusion—and you invite the possibility of an unnecessarily painful or drawn out decision process.

Decision Point 3: The Right Process. Will you flip a coin? Throw darts? Check with your boss? Make decision tables? Use a decision tree or a bubble chart? Build a business case? It would depend on the decision situation. Making a high quality decision doesn’t have to be time consuming. In some cases, the best process might just be a coin toss or relying on some rules of thumb. In other cases, the only way to work a decision is to really work it, and that will take time.

The only rule is that the mechanics of how you’ll work the decision to conclusion need to be appropriate to the size, significance, and complexity of the decision. How long is too long? When the cost of working the decision any further outweighs the benefits of making a choice.

This element of declaration pulls the frame and people together into a coherent whole that will govern how you will reason this decision through.

Work

Decision Point 4: A complete set of alternatives. “The more options you generate, the greater your chance of finding an excellent one. You should only stop generating more options when the cost and delay of further search are likely to exceed the benefit.” (Russo)

What is the right number of alternatives? That depends on how you’ve framed the question. Two terms are helpful in this regard. “Collectively exhaustive” means that the alternatives you’re considering fill the frame: a rational observer would conclude that you’ve thought of everything that matters. “Mutually exclusive” means that the alternatives are unique and different from each other: they’re not just restatements of the same choice.

Decision Point 5: Values against which to make tradeoffs. Values define your preferences among alternatives. They are your criteria. Values can be expressed by “attributes.”Attributes are characteristics of the outcomes that we find desirable or undesirable. They typically occur over time and may have some degree of uncertainty associated with them.

For each decision, particularly those involving others, you need to make your definition of value visible, clear, and distinct. In commerce, the acid test of a value is often that you can measure it.

Decision Point 6: Information that describes the value of each alternative. Good decision-making requires not only knowing the facts, but understanding the limits of your knowledge. The most valuable insights are often found in exploring uncertainties and “disconfirming” information. “The effective decision does not, as so many texts on decision-making proclaim, flow from a consensus on the facts. The understanding that underlies the right decisions grows out of the clash and conflict of divergent opinions and out of the serious consideration of competing alternatives.” (Peter Drucker, The Effective Executive)

You can wear yourself out gathering and analyzing information. What you want is insight that will help you judge the relative and comparative value of the alternatives you’re considering.

Leaders should focus on creating the dynamics that support organizational decision quality—on putting in place a decision framework and process that supports organizational decision quality—rather than raking through the detailed minutia of specific decisions. A high quality decision process highlights the frame, potential alternatives, and key assumptions the drive value. This allows leaders to spend their time declaring the right decisions, providing a set of common criteria, and testing the key assumptions of each decision.