Источник: http://www4.ncsu.edu/~kkc/papers/rev2.pdf

Scheduling Hadoop Jobs to Meet Deadlines

Kamal Kc, Kemafor Anyanwu Department of Computer Science North Carolina State University {kkc,kogan}@ncsu.edu

Abstract—User constraints such as deadlines are important requirements that are not considered by existing cloud-based data processing environments such as Hadoop. In the current implementation, jobs are scheduled in FIFO order by default with options for other priority based schedulers. In this paper, we extend real time cluster scheduling approach to account for the two-phase computation style of MapReduce. We develop criteria for scheduling jobs based on user specified deadline constraints and discuss our implementation and preliminary evaluation of a Deadline Constraint Scheduler for Hadoop which ensures that only jobs whose deadlines can be met are scheduled for execution.

I. INTRODUCTION

Apache Hadoop is an open source implementation of Google’s MapReduce [4] that has gained significant popularity as a platform for large scale data processing applications. MapReduce is a parallel data processing paradigm targeted at cluster-based computing architectures. Its advantage is that it allows programmers to abstract from the issues of paralleliza-tion, scheduling, input partitioning, failover, replication and focus on designing their application data flows consisting of filtering and aggregation steps. The MapReduce programming model consists of encoding data processing in terms of two functions: Map and Reduce. Input data is partitioned into fixed sized blocks and fed into parallel Map tasks which process the data chunks and produce intermediate output as a collection of key-value pair tuples. These tuples are shuffled across different reduce nodes based on key values. Each Reduce task performs three steps: copy - the map output is copied to reducer nodes, sort - the collected map output is sorted based on key values and reduce - reduce function e.g. aggregation is applied to the data. Various efforts like Hive [5], Pig[11] offer friendlier interfaces in the form of high level query or dataflow languages a la SQL. This enables users to encode their tasks in terms of query operators that are automatically compiled into Hadoop jobs (MapReduce workflows) instead of as low-level Map and Reduce functions.

The MapReduce architecture consists of one master (Job-tracker) and many workers (Tasktrackers). The JobTracker receives job submitted from user, breaks it down into map and reduce tasks, assigns the tasks to Tasktrackers, monitors the progress of the Tasktrackers, and finally when all the tasks are complete, reports the user about the job completion. Each Tasktracker has a fixed number of map and reduce task slots that determine how many map and reduce tasks it can run at a time. The Hadoop File System HDFS supports reliability and fault tolerance of MapReduce computation by storing and replicating the inputs and outputs of a Hadoop job. Since Hadoop jobs have to share the cluster resources, a scheduling policy is used to determine when a job can execute its tasks. The default scheduling policy of Hadoop is First In First Out (FIFO). Under this scheme, the job that was submitted earlier gets preference over jobs submitted later. Recent efforts such as Delay Scheduler[15], Dynamic Proportional Scheduler [13] offer differentiated service for Hadoop jobs allowing users to adjust the priority levels assigned to their jobs. However, this does not guarantee that the job will be completed by a specific deadline. [12] comes close to addressing the issue of deadlines but focuses more on increasing system utilization. [14], [9] focus on supporting deadline constraints in traditional parallel computation models which differ from the two-phase computation and unique dataflow of MapReduce jobs. [1] considers deadline constraints in the context of real time transactions in single processor environments.

In this paper, we lay the foundation for dealing with deadline requirements in Hadoop-based data processing by (1) proposing a job execution cost model that accounts for the various parameters that affect Hadoop job completion time such as map and reduce runtimes, map and reduce input data sizes, data distribution, etc., (2) presenting the design of a Constraint-Based Hadoop Scheduler that takes user deadlines as part of its input and determines the schedulability of a job based on the proposed job execution cost model and does so independent of the number of jobs running in the cluster. Jobs are only scheduled if specified deadlines can be met. We focus on deadline constraints when MapReduce runtime parameter values are known and leave the issue of estimating job parameter values as future work. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: in section II, we discuss the scheduling aspects of the problem and derive expression for minimum map/reduce task allocation required to meet deadlines. In section III, we present the design and implementation of Constraint Scheduler and in section IV, we present results for task allocation for different deadlines.

II. FOUNDATIONS

A. Problem Definition

Problem Statement: Can a given query q that translates to a MapReduce job J and has to process data of size a be completed within a deadline D, when run in a MapReduce cluster having N nodes with Nm map task slots, Nr reduce task slots and possibly k jobs executing at the time.

Executing query q in the MapReduce framework involves scheduling the corresponding map and reduce tasks of job J.

While it is possible for q to translate to a sequence of MapRe-duce jobs, in this paper, we focus on queries that translate to a single MapReduce job. After a job is submitted, the scheduler first needs to determine whether the job can be completed within the specified deadline or not using a schedulability test. Rather than make schedulability determination based on all the jobs running in the system, we focus on the free slots availability at the given time or in the future. After it is determined that the job can be completed within the given deadline, it is enlisted for scheduling. An important issue is then to assign the right number of tasks to the Tasktracker to ensure that the deadline is met. Some strategies include:

• Assign all map and reduce tasks: Assigns all the tasks if the number of tasks is less than the total available slots. If not, it assigns the tasks to all the available slots in the cluster. This may result in jobs submitted later not having enough slots to run.

• Assign minimum tasks: Assigns only minimum number of tasks required for a job to meet its deadline. Empty slots may be available for jobs submitted later.

• Assign some fixed number of tasks.

For the rest of paper, “minimum number of tasks” will be used to refer to the minimum number of tasks required for a job's schedulability independent of task assignment approach. A job is schedulable if the minimum number of tasks for both map and reduce is less than or equal to the available slots. We show the derivation for the minimum number of map and reduce task in the following subsections.

B. Deadline Estimation Model

We develop an initial estimation model based a set of assumptions which will be relaxed later in the discussion: (1) the cluster consists of homogeneous nodes, so that the unit cost of processing for each map or reduce node is equal; (2) key distribution of the input data is uniform, so that each reduce node gets equal amount of reduce data to process;

(3) reduce tasks starts after all map tasks have completed;

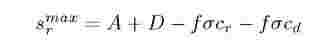

(4) the input data is already available in HDFS. To derive the expressions for the minimum number of map tasks n™" and reduce tasks n™", we extend the model used in[9] for Equal Load Partitioning technique by introducing MapReduce specific notations J, f , cm, cr, sm and sr as described below:

To estimate the duration of the job J we consider map completion time, reduce completion time and data transfer during reduce copy phase. The expression for the cost can be written as:

Since the job has an arrival time A and deadline D,

Our constraint scheduler uses this criteria to schedule Hadoop jobs.

1) Invalidating Assumptions:

• Assumption 1. We assumed that nodes are homogeneous and the value of cm and cr was uniform for all the nodes. To relax this assumption we allow for the value of cmand cr to differ among the nodes making the job dependent on the slowest node i.e. the value of cm and cr is the highest. Therefore, we modify the above expressions for nrmm , nm" and smax by substituting cm and cr with the value of the slowest running node.

• Assumption 2: When the key distribution across the reduce tasks is not uniform, then the worst case is that a single node processes all the reduce input fa. In such scenario, the value of srmiax will be:

We intend to address in our future work the effect of various data distribution models. Starting reduce tasks early might affect other jobs ability to obtain reduce task slots. In

this paper, we do not address the implications of invalidating Assumption 3. We think it is relevant to assume that the input is available in HDFS because MapReduce processing starts only after the data is available. If it becomes important to consider the cost of transferring the input to HDFS from user's storage, the cost can be derived using the values for transfer network link capacity and the replication cost, and these costs are not dependent on the nature of MapReduce job.

III. Design and Implementation

Hadoop supports pluggable schedulers and we have implemented Constraint scheduler using the minimum task scheduling criteria developed in the previous section. It is developed as a contrib module using Hadoop version 0.20.2 source code. Hadoop config file needs to be modified to use the scheduler. We have also implemented a web based interface that allows the user to specify the deadline for a given job.

A. Design Goals

The design goals for Constraint Scheduler were: (1) To be able to give users immediate feedback on whether the job can be completed within the given deadline or not and proceed with execution if deadline can be met. Otherwise, users have the option to resubmit with modified deadline requirements. (2) Maximize the number of jobs that can be run in the cluster while satisfying the time requirements of all jobs.

When a job is submitted, we perform its schedulability test similar to that mentioned in [9]. We first calculate the minimum map tasks for the submitted job. If the minimum map tasks are not available at the time when job was submitted then the job is rejected. We then calculate srmiax based on the total number of reduce tasks specified for the job. As mentioned earlier, the number of reduce tasks for a job is user defined or is a default value. If the number of reduce task slots available at srmiax is not equal to the specified number of reduce tasks for the job then also the job is rejected. An alternative to rejecting a job strictly based on srmiax would be to compute a suitable sr value so that the required number of reduce tasks slots would be less than the job specified number. We intend to explore this aspect in our future work. After a job is scheduled and map tasks are complete, uimin is computed to determine how many reduce tasks should be scheduled. Since, sr < s'max , this allows for cases when n'lnin can be less than the reduce tasks specified for the job. This increases the potential of keeping some reduce slots empty.

Another design goal is to maximize the number of jobs while satisfying the deadlines. There have been arguments for and against it when using the minimum tasks scheduling approach for multiprocessor and cluster computing environment as mentioned in [8],[9]. Arrival rates of the job may play an important role in determining this. Intuitively, when jobs are scheduled using only minimum number of tasks then it leaves slots empty for later jobs to execute. We, however do not quantitatively evaluate it in this paper.

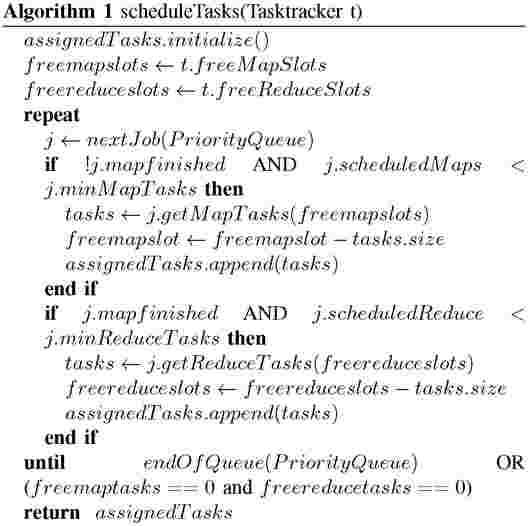

B. Task Assignment and Runtime

Map and reduce tasks runtime values are required to derive the minimum node criteria. In our implementation we use static values. A user can supply the map and reduce task runtime values using the web interface. In our future work we intend to explore techniques for task runtime estimation such as cost model for MapReduce code and estimating cost using a short sampled job. Recent work such as Manimal [3] have explored static code analysis techniques for MapReduce code. Task assignment is done in reply to the heartbeat obtained from the Tasktrackers. The heartbeat interval is 3 seconds by default. Constraint Scheduler maintains a priority queue of the jobs ordered by their deadlines. Tasks scheduling is first attempted for jobs that is at the front of priority queue. If a job's minimum task count is satisfied then we consider next job until there is no more jobs remaining in priority queue or until there are no more unassigned map/reduce slots remaining for the Tasktracker. There can be Tasktrackers which may not be assigned any tasks if the minimum task count is satisfied for all the jobs. Algorithm 1 presents this technique for scheduling tasks. The scheduling algorithm assigns reduce tasks only after all the map tasks have been completed. This is in accordance with our assumption in previous section.

IV. EVALUATION

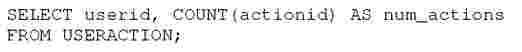

To evaluate the Constraint Scheduler we ran Hadoop job that represented aggregation operation, which is one of the common type of operation performed by MapReduce. MapRe-duce job equivalent to the following query was used for the experiment.

The useraction table contains

tuples (userid,actionid). The map task of the job

parses the input and outputs (userid, actionid) as key-value pairs. The reduce task then counts the number of actionid for each userid. The filterratio for this MapReduce job is 1. The generated data used for the experiment had uniform distribution across the key - userid, resulting in reducers getting equal amount of data to process. We have not considered map and reduce task startup overhead in our experiments. We also do not consider the failure rate of the cluster in the experiments. Data transfer time was estimated using iperf [6] by performing communication between all Jobtracker and Tasktrackers. We evaluate the task assignment behavior of Constraint Scheduler for different deadlines. Our observations are described below.

A. Experimental setup

Experiments were conducted in two different cluster environments: virtualized cluster and physical cluster. The virtualized cluster consisted of a single physical node with 3 guests as Tasktrackers and the host system as Jobtracker. The machine had 4 GB memory with 64 bit Intel dual core 2.93GHz processor and Ubuntu server present in each virtualized nodes. The physical cluster was all node cluster reserved using VCL [7] where 10 were Tasktrackers and 1 was Jobtracker. Each node specification was: 4GB main memory, Intel 2.33 GHz processor running Redhat Enterprise Linux. Hadoop version 0.20.2 was used in the virtualized cluster and version 0.20.1 was used in the physical cluster. Both the environments had Tasktrackers with 2 map slots and 2 reduce slots. Other than changing the scheduler, all other configuration parameters were default values. The HDFS block size was 64 MB. The measured network capacity was 12MB/s.

B. Results

In the virtualized nodes, we observed that the task execution time varied depending upon how many nodes were currently executing the map tasks. This was due to cpu sharing between the virtualized nodes. Virtualization is one of the scenarios when heterogeneity exists among nodes. We accounted for heterogeneity in problem formulation section by using the execution time of the slowest node in our minimum task criteria. We observed the task execution time varying from 37 seconds to 120 seconds. We selected the largest execution time as our estimate.

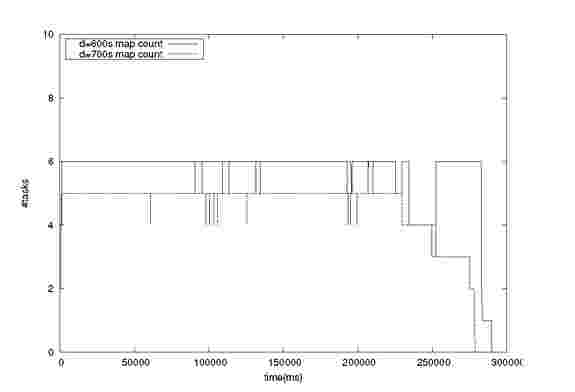

Figure 1 shows the map task allocation results for the same job when submitted with different deadlines. The input size was 975MB which resulted in 16 map tasks. The cluster capacity was 6 map tasks and 6 reduce tasks. We observe that the tasks allocation is done differently for the two deadlines. For 600s deadline, 6 map tasks is scheduled at a time. For 700s deadline, 5 map tasks are scheduled. The number of map tasks scheduled is the minimum tasks value derived by the scheduler. Interestingly, we also notice that the map tasks for deadline 700s finishes earlier than the map tasks for deadline 600s. This is due to the increased map completion time for deadline 600s, as it tries to schedule more map tasks and that results in increased per map completion time though it is within the initial estimate we provide. The increase in per map

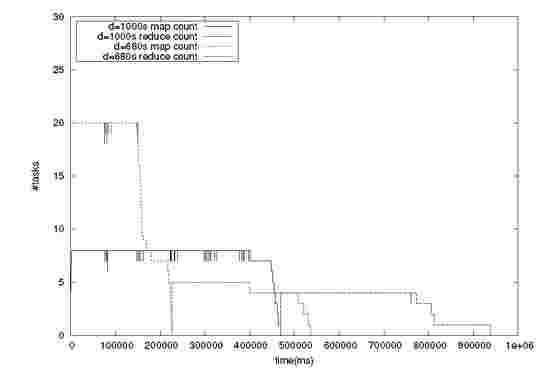

Figure 2. Map and reduce task allocation for jobs with deadlines 1000s and 680s in cluster with physical hosts

completion time is due to the cpu sharing among virtualized nodes as described previously. Job with deadline 700s tries to schedule less map tasks which results in better map completion time and hence it finishes faster. The above result was obtained by executing the jobs when the cluster had no other running jobs. The transient spikes seen in Figure 1 correspond to the time interval during which a task has finished but the task’s assigned Tasktracker or any other Tasktracker with empty slot has not sent heartbeat request.

Figure 1. Task allocation for jobs with deadlines 600s and 700s in cluster with virtualized hosts

Similarly, Figure 2 shows the task allocation results for the same job running on the physical cluster with deadlines of 1000s and 680s. The input size was 2.9 GB which resulted in 48 map tasks. The cluster capacity was 20 map tasks and 20 reduce tasks. For 680s deadline, 20 map tasks and 5 reduce tasks are scheduled. For 1000s deadline, 8 map tasks and 4 reduce tasks are scheduled. In both the cases, the deadlines are met and Constraint Scheduler ensures that the minimum task count is met during the entire job execution.

To meet the minimum task criteria, a task may be assigned to Tasktracker even though the data is non local to it. We have not accounted this in our minimum tasks criteria. Since, in these experiments the task count is less and also that we have used the observed worst case computation time, the data transfer cost due to non local computation seems to be hidden. However, it’s impact in scenarios involving larger number of tasks remains to be investigated. Also, our basic model includes the cost of copy phase of reducers but does not separately account for sort phase. During the experiment, we have assumed that the reduce cost also includes the sort cost.

V. Related Work

MapReduce scheduling and time estimation: Until recently, options for scheduling tasks in Hadoop were limited to the default FIFO scheduler, FairScheduler [15] and Capacity Scheduler. Latter two and recent research effort Dynamic Proportional Scheduler [13] provide more job sharing and prioritization capability in scheduling resulting in increased sharing of cluster resources and more differentiation in service levels of different jobs. Time estimation and optimization for Hadoop jobs has been explored by [2],[10]. [2] focuses on minimizing the total completion time of a set of MapReduce jobs. [10] estimates the progress of queries that run as MapReduce DAGs. Most efforts on scheduling focus on handling various priority and most time estimation efforts are focused on runtime estimation of already running jobs. The closest effort to our work is [12] which proposes a scheduler that tries to increase system resource utilization by attempting to honor time constraints similar to a deadline scheduler. However, they do not consider the schedulability of a job prior to accepting it for execution. Also, their work emphasizes map tasks and does not model the reduce computation. Our work attempts to cover these aspects and puts more emphasis on meeting deadlines in the shared cluster environment.

Scheduling database transactions: In [1], the authors evaluate transactions that have real time constraints for single processor memory resident database systems. The authors use estimated execution time for determining the Feasible Deadline which determines whether a deadline will be met or not. For scheduling, they use Earlier Deadline First (EDF) and Least Slack method. Our work builds around obtaining the execution estimate (in our case estimate of map and reduce computation).

Scheduling under constraints: A genetic algorithm for task assignment in grid-based environments is used in [14]. The scheduling problem here is the mapping of tasks onto a suitable service level to minimize the execution time of a workflow and complete it within a given budget. [9] explores the scheduling of divisible real time tasks in a cluster environment. A divisible task refers to a task that can be divided into multiple independent subtasks each of which will process a piece of input data. Its data partitioning using Equal Partitioning Rule and task/subtask concept can be considered to be analogous to Hadoop. The authors derive an expression for the minimum number of nodes required to meet a deadline. Though similarities with our work exist in task assignments and data partitioning, their work assumes a single type of computation whereas Hadoop has two types of computations: map and reduce. Map input data size can be determined when a job is submitted but the reduce input size is not known without considering the key distribution. Also, map computations are almost uniform in homogeneous environment but reduce computation vary depending upon the size of input a reduce task receives. Consequently, our work extends their basic deadline determination criteria to account for the MapReduce style of computation.

VI. Conclusion

In this paper, we extended the real time cluster scheduling approach to derive minimum map and reduce task count criteria for performing task scheduling with deadline constraints in Hadoop. We presented the design and implementation of Constraint Scheduler for Hadoop following the proposed approach. Our results show that when deadlines for job is different, then the scheduler assigns different number of tasks to Tasktracker and makes sure that the specified deadline is met. In this work, we have left out aspects of Constraint Scheduler such as map/reduce task runtime estimation, filterratio estimation, data distribution and multiple MapReduce cycle support. We plan to address these topics in our future work.

References

[1] Robert K. Abbott and Hector Garcia-Molina. Scheduling real-time transactions: a performance evaluation. ACM Trans. Database Syst., 17(3):513-560, 1992.

[2] Ashraf Aboulnaga, Ziyu Wang, and Zi Ye Zhang. Packing the most onto your cloud. In CloudDB ’09: Proceeding of the first international workshop on Cloud data management, pages 25-28, New York, NY, USA, 2009. ACM.

[3] Michael J. Cafarella and Christopher Re. Manimal: Relational optimization for data-intensive programs. In WebDB, 2010.

[4] Jeffrey Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat. Mapreduce: simplified data processing on large clusters. In OSDI’04: Proceedings of the 6th conference on Symposium on Opearting Systems Design & Implementation, pages 10-10, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. USENIX Association.

[5] Hive. http://hadoop.apache.org/hive.

[6] Iperf. http://iperf.sourceforge.net/.

[7] Virtual Computing Lab. http://vcl.ncsu.edu/.

[8] Wan Yeon Lee, Sung Je Hong, and Jong Kim. On-line scheduling of scalable real-time tasks on multiprocessor systems. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput., 63(12):1315-1324, 2003.

[9] Xuan Lin, Ying Lu, J. Deogun, and S. Goddard. Real-time divisible load scheduling for cluster computing. In Real Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, 2007. RTAS ’07. 13th IEEE, pages 303 -314, 3-6 2007.

[10] Kristi Morton, Magdalena Balazinska, and Dan Grossman. Paratimer: a progress indicator for mapreduce dags. In SIGMOD ’10: Proceedings of the 2010 international conference on Management of data, pages 507-518, New York, NY, USA, 2010. ACM.

[11] Pig. http://hadoop.apache.org/pig/.

[12] Jorda Polo, David Carrera, Yolanda Becerra, Malgorzata Steinder, and Ian Whalley. Performance-driven task co-scheduling for mapreduce environments. In Network Operations and Management Symposium (NOMS), 2010 IEEE, pages 373 -380, 19-23 2010.

[13] Thomas Sandholm and Kevin Lai. Dynamic proportional share scheduling in hadoop. In JSSPP ’10: 15th Workshop on Job Scheduling Strategies for Parallel Processing, 2010.

[14] Jia Yu and Rajkumar Buyya. A budget constrained scheduling of workflow applications on utility grids using genetic algorithms. In Workshop on Workflows in Support of Large-Scale Science, Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Symposium on High Performance Distributed Computing (HPDC. IEEE, IEEE CS Press, 2006.

[15] Matei Zaharia, Dhruba Borthakur, Joydeep Sen Sarma, Khaled Elmele-egy, Scott Shenker, and Ion Stoica. Delay scheduling: a simple technique for achieving locality and fairness in cluster scheduling. In EuroSys '10: Proceedings of the 5th European conference on Computer systems, pages 265-278, New York, NY, USA, 2010. ACM.